A brief but important artistic era that bridges the fin de siècle of the 19th and 20th centuries; this is the brave new style of Art Nouveau.

What is Art Nouveau?

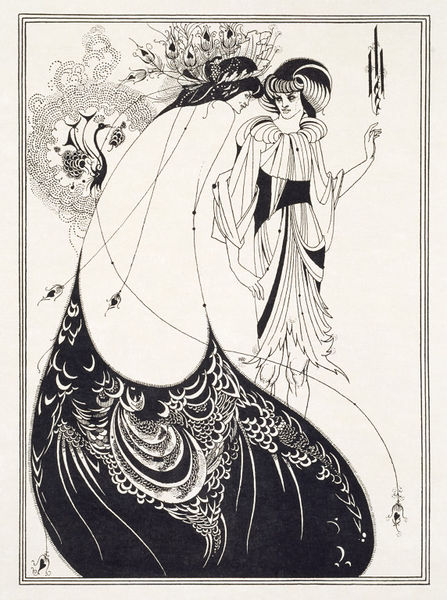

Art Nouveau can be distinguished from other art styles by its primary use of long, winding lines and the natural world as its major source of inspiration. Its colours are muted, blending soft organic shades within heavy contours.

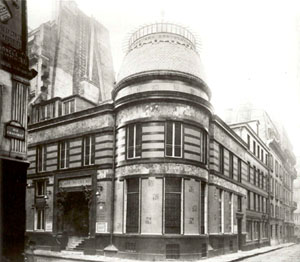

Art Nouveau is a French term literally translating as “new art”, symbolising a significant break from the art styles before it. The name was taken from the art gallery Maison de l'Art Nouveau (or the House of New Art) in Paris ran by Siegfried Bing. Bing was a Franco-German collector of avant-garde art that had an eye for Japanese works. His establishment of this gallery in 1895 served as the epicentre of Art Nouveau’s impact. Modern furniture and decor were on display alongside objets d’art.

Art Nouveau was a movement in the art world born in response to the established dominance of classical styles and their rigid formal structures throughout the 19th century. Proponents thought to put the decorative arts on the same level as the fine arts in terms of respect and reverence.

It was the style that was most popular between 1890 to 1910, taking on different names across countries in the Western world. These regional forms had specific characteristics that defined the movement in those areas.

Art Nouveau’s Foundations Around the World

While the name takes its source from a gallery in France, Art Nouveau had its start in Britain. British designer William Morris pioneered the Arts and Crafts movement in 1880, which was one of the major inspirations for Art Nouveau. Morris’ penchant for floral patterns and admiration for the work of craftsmen can be seen as pillars to the philosophies of Art Nouveau.

Within the UK, Art Nouveau was known more as Modern Style. The Glasgow School in Scotland was the major force in the country’s expression of Art Nouveau architecture.

With the burgeoning cultural trade between East and West at the time, Japanese art was a major influence in shaping Art Nouveau. Woodblock prints from Japan and their signature “whiplash” curves captured the imagination of European artists. Katsushika Hokusai, Utagawa Hiroshige, and Utagawa Kunisada were the biggest influencers of Japonism.

Style moderne was an alternate name for the aesthetic in France. The cities of Paris and Nancy were where the style proliferated the most. This can be seen in the ornamented buildings, restaurants, and cafes.

In Germany, the style was called Jugendstil or “youth style” after the art magazine Die Jugend started by George Hirth in 1896. This periodical was critical in propagating Art Nouveau throughout the country, particularly in the realm of graphic design. Austrian artists developed a style akin to Jugendstil called Secessionsstil or the Vienna Secession.

Stile Liberty was what Art Nouveau was known as in Italy. The name was taken from the British department store Liberty & Co.

Over in Spain, people knew it as Modernismo or Modernisme (in Catalan), which had its distinct flair based on a special interest in Catalan nationalism.

Belgian artists called it Style nouille or Style coup de fouet. Architect Victor Horta was at the forefront of the movement in Belgium.

Nieuwe Kunst was the name in the Netherlands. This “New Art” was expressed in architecture toward the two extremes of functionality and ornamentation.

Still modern was the style that was popularised in Russia, specifically in Moscow and Saint Petersburg, through the publication of “The World of Art” in 1898. This manifestation of Art Nouveau was inspired by Russian folklore.

In the United States of America, artist and designer Louis Comfort Tiffany led the Art Nouveau movement through his glass work. His firm’s strong reputation and the prevalence of their products led to Art Nouveau being known as Tiffany Style in the US.

Art Nouveau in the Visual Arts

Textiles played a significant role in popularising Art Nouveau. Liberty & Co. sold plenty of textiles featuring floral designs and nature-based geometric forms. Many of these designs came from the minds of William Morris, Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, the Silver Studio, and the Glasgow School.

Eugene Grasset’s La Plante et ses applications ornamentales was the authoritative book on the use of plant life as decorative motifs. Folklore also inspired many creative designs on decorative items such as tapestries and embroideries.

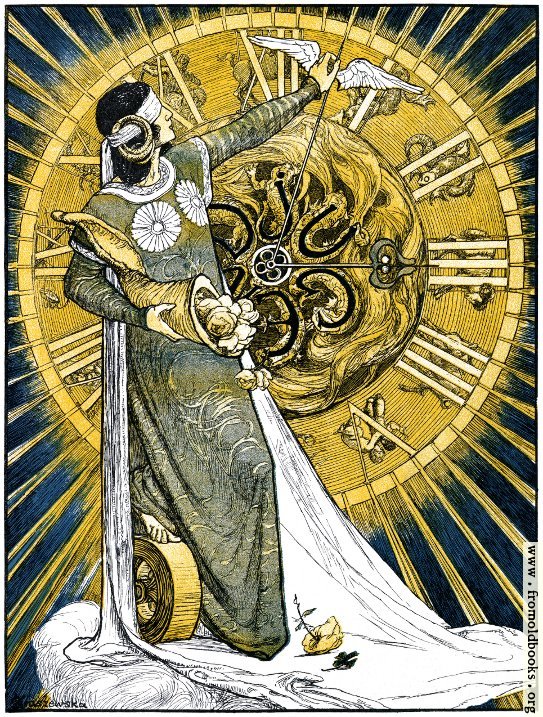

Another vector for the mainstream acceptance of Art Nouveau was graphic design. With the advent of colour lithography in 1798, coloured posters got more widespread use in advertising. This coincided with the rise of retail department stores. Artists designed these posters in the Art Nouveau style, mostly showcasing glamourised women surrounded by flowers. Book covers and magazine illustrations had to catch and keep readers’ eyes with intricate patterns drawn in bold, sinuous lines.

Aubrey Beardsley of Britain, Eugene Grasset of France, Alphonse Mucha of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Koloman Moser of Vienna were some of the biggest names in Art Nouveau graphic arts.

The advances in glassmaking techniques--such as acid etching, glassblowing, colouring, and encrusting--proved vital to Art Nouveau’s proliferation in glass art.

Emille Gallé and the brothers Auguste and Antonin Daum led the glassworking scene in France with their vase and art glass designs. These artists were based in Nancy, where the Art Nouveau houses also had flower-patterned stained glass windows.

Louis Comfort Tiffany’s glass colouring innovation led to the radiance emanating from Favrile glass lamp shades. This technique highlighted the harmony of fine and applied arts that Art Nouveau espoused.

As the movement sought to equalise the fine arts and the decorative arts, painting took on a more practical role. It complemented architecture, interior design, and by extension, furniture design. This resulted in a cohesive look to buildings inside and out, reflecting a strong vision of beauty in every piece that made up the whole. When there were paintings explicitly created as their own single work, they depicted fanciful femininity.

Gustav Klimt was one of the main painters of the Vienna Secession branch of Art Nouveau. He adorned the interiors of Viennese architecture with his painting mastery.

Ceramic crafting saw technological breakthroughs, East Asian influence, and architectural application during this period. Hydrofluoric acid etching and the matte glaze were some of the techniques trending at the time.

China and Japan’s flower-laden designs for their ceramics crossed over into Europe’s pottery patterns. Alexandre Bigot’s company made terracotta tiling and decor for building exteriors and interiors.

Art Nouveau Architecture

Architect and historian Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc published Entretiens sur l'architecture in 1872, wherein he advocated for “a new architecture” based on then-modern technology and the unity of decoration and function. This belief was echoed throughout the Art Nouveau architecture movement.

As the Industrial Age birthed cities with big, boxy buildings, architects sought to infuse the beauty of nature into their designs while taking advantage of complex crafting techniques.

Facades featured all sorts of decorations in the form of flowers, plants, and animals. Asymmetry was embraced in opposition to the uniform look of buildings past. Residences, business establishments, and public institutions were made to look as if they had grown from the ground up.

The whiplash line work of the time’s visual arts were incorporated in the parabolic and hyperbolic arches, as well as the organic ornamentation. Exposed wrought iron and glass moulded into natural shapes accentuated the exteriors, evoking a sense of movement and life. Terracotta sculptures and ceramic tiles lined the insides with warmth and colour.

These embellishments were treated just as critical to the structure as every brick and mortar in accomplishing Art Nouveau's design goals. The buildings and their adornments were seen as one.

Victor Horta was the foremost architect of the style in Belgium. His designs for Hôtel Tassel and Hôtel Solvay in Brussels were structural odes to vegetation and how it shifts and takes space on the earth.

French architect Hector Guimard drew inspiration from Horta’s work after visiting Hôtel Tassel. Guimard would apply similar principles to his design of the Castel Béranger, a lavish flat in Paris. The government of France then commissioned him to work on the entrances of the Paris Métro, which was scheduled to open in 1900. The intricate glass and iron work that resemble seed pods and bean shoots greet Parisian commuters to this day.

Antoni Gaudi of Barcelona, Spain is another titan of Art Nouveau architecture. Casa Mila combines stone and iron into controlled curvilinear chaos. Casa Batlló stands like an otherworldly edifice with its curved iron and glass veneer, fitting for its name as “the House of Bones”.

Across the Atlantic, Louis Henry Sullivan made his mark on architectural history with his vegetal and honeycomb designs for the Wainwright Building, the Guaranty Building, and the Chicago Stock Exchange.

Ålesund, Norway suffered major fires in 1904, so the town was rebuilt almost entirely in the Art Nouveau style.

Art Nouveau Fashion

Art Nouveau’s influence on fashion is tied to the rise of prestigious Parisian couture houses. The Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne organised a business structure that proper couture houses would follow. This led to a cooperative effort of promoting Paris as the pre-eminent force in fashion. As this happened during the Art Nouveau movement, the style was reflected on the couturiers’ designs, which only the global elite had the privilege of wearing.

Couturiers poured their Art Nouveau sensibilities the most into evening wear. Evening dresses fell under the realm of decorative art, displaying intricate floral embroidery, appliqué, and lace trimmings. The S-curve was still a popular silhouette, and it lent itself perfectly to the sinuous “New Art” aesthetic.

There was a shift to a softer, more natural figure that did away with the tight corset. Gender ambiguity and comfort were design goals, with couturiers for women looking to tailored men’s wear for inspiration.

The renowned designers of the period were Jean-Philippe Worth of the House of Worth, Paul Poiret, and Jeanne Paquin among others. Their work exemplified the luxury, beauty, and experimentation of Art Nouveau fashion.

Authoritative fashion magazines like Les Modes, La Mode Illustrée, and The Ladies Field were important in spreading the clothing style to upper and middle-class women.

Art Nouveau Jewellery

The themes of Art Nouveau jewellery followed the overall style of the movement. Flora, fauna, and the feminine form were celebrated. The design and the blending of colours surrounding gemstones were as important, if not more so than the precious stones themselves. Jewellers weren’t constrained to typical pieces and put their skill to beautifying accessories like fans, pocket watches, and combs.

Popular nature motifs were birds and winged insects like butterflies and dragonflies. Women featured heavily on extravagant pieces like necklaces with pendants and subdued works like cameos, taking on fantastical and even eroticised forms. Long, flowing hair served as the striking, curved lines that defined Art Nouveau.

Diamonds were the main attraction for jewellery in previous eras, but they gave way to more colourful gemstones like agate, aquamarine, and opal during the Art Nouveau movement. Baroque pearls were in vogue as well for their eye-catching size and shape. Materials like heated horn and carved ivory were used to create novel pieces.

Enamelling also became more prominent. The plique-à-jour technique of enamelling allowed for light to pass through the enamel, adding translucency to the design.

René Lalique was the most prolific jewel designer of the time. He was an apprentice of Louis Aucoc, an important figure in early Art Nouveau jewellery and whose Parisian studio was highly respected in the industry.

Lalique owed much of his success to stage and film actress Sarah Bernhardt’s patronage of his pieces. Bernhardt’s celebrity linked Lalique’s jewellery to fame and fortune. The excess that oozed from Lalique’s pieces, as well as his contemporaries, meant that people of high society, like Bernhardt, were the only ones that could afford such luxurious items.

This association with affluence, not to mention their fragility, made Art Nouveau jewellery as much of a quickly passing trend as the style movement at large. Only a select few got to wear them, and they were much easier to set aside and viewed as objet d'art.

Art Nouveau’s Abrupt End

The pursuit of beauty in craftsmanship and prioritisation of ornamentation in Art Nouveau eventually led to decorative designs going overboard in the eyes of critics. It was deemed too lavish to the point of frivolity. The masses had little to no access to works produced in the style, failing to affect much change in how art was viewed by everyday people.

Art Nouveau was soon abandoned before World War I and was followed by the simpler designs and broader appeal of Art Deco that emerged in the interwar period of the 1920s and 30s.