When Queen Anne died in 1714 having borne no children, the Act of Settlement 1701 demanded the successor to the throne be Protestant and Hanoverian. Thus, the Elector of Hanover became King George I. And so began the Georgian Era.

This period in British history saw the reign of four Hanoverian Kings, all named George. That is, until 1830 when William IV succeeded his brother George IV, and ruled until his death in 1837, effectively ending the Georgian Era.

A Primer on The Georgian Era

This was a tumultuous period in British history, as the monarchy immediately faced internal opposition from the Scottish Jacobites over proper succession. The kingdom waged numerous wars with rival nation France and fought the Thirteen Colonies that would become the United States of America.

The empire expanded across the globe through the power of the Royal Navy and the exploitation of the Atlantic slave trade. During this period Britain kickstarted the Industrial Revolution, which would change the world forever. This went hand in hand with developments in the ongoing agricultural revolution that led to massively higher crop yields and the ability to feed a growing population.

The arts and fashions of the times had their fair share of contrasts. Romanticism emerged as a reaction to the rationalism of the Enlightenment, favouring the beauty in emotion and nature. This was soon, however, critiqued by the Realist movement.

The elegance of Classical architecture was followed by the intricacy of the Gothic Revival. Women’s clothing flowed freely, while men had their outfits cut to a closer fit. Jewellery, meanwhile, differed starkly from day sets to evening accessories.

Defining British Art in the Early 18th Century

Economic prosperity would become a hallmark of the era, but Georgian rule also began with commercial disaster. The South Sea Company, a joint-stock company made for South American trade, crashed in 1720 and disgraced numerous politicians and investors.

Artist William Hogarth started making waves as a satirist and social critic with his engraving The South Sea Scheme, which depicted the corruption that caused the South Sea Bubble.

Hogarth would eventually become one of the most famous and influential artists of the era, well-known for his portraiture, sequential art, and moralising art that commented on sexuality, love, work, and the gin epidemic that consumed the public in the early to mid 18th century. The burgeoning purchasing power of the middle class contributed greatly to Hogarth’s popularity.

As it was in the arts, satire and political commentary were the defining literary genres of the time. Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope stood as giants of the era for prose and poetry, respectively.

The novel started coming into critical acceptance during the Georgian period. Daniel Defoe pioneered the form with his acclaimed Robinson Crusoe (1719), while Samuel Richardson and Henry Fielding argued between the impact of the individual and society on each other through their novels Pamela (1740), Shamela (1742), and other works.

Defining British Art in the Mid to Late 18th Century

The British Agricultural Revolution increased food production, caused population growth to explode, and eventually gave way to the Industrial Revolution. This, in turn, boosted productivity even higher and rapidly developed urban living through the creation of factories, transforming Britain into the world’s first industrial nation by 1760.

The latter half of the 18th century saw the rise of great English painters: Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough. George III founded the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768, with Reynolds serving as academy president and the king’s principal painter.

Reynolds and Gainsborough’s rivalry bolstered the art of portraiture in the public eye, particularly among the nobility, while developing landscape art in their personal time.

Samuel Johnson published A Dictionary of the English Language in 1755, a seminal work that shaped Modern English. The sentimental novel and Gothic fiction rose to prominence as precursors to Romanticism, as did the novels of manners, which would later influence Jane Austen.

Defining British Art in the Early 19th Century

The last major conflict Britain engaged in during the Georgian Era had the kingdom leading coalitions against the French Empire in the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815).

The economy slumped in the postwar years followed by political unrest and government repression. This climaxed with the Peterloo Massacre of 1819, where cavalry charged into 60,000 protesters demanding parliamentary reform (an event recently portrayed in Mike Leigh’s critically acclaimed film). Legislative change did come when the economy started recovering at the beginning of the 1830s, including the abolition of slavery and the Great Reform Act of 1832.

J.M.W. Turner and John Constable led the Romantic movement in painting and left an indelible mark on English visual arts with their encapsulation of nature’s beauty and power through impressionistic landscapes. William Blake was a singular talent of the period for his mastery of poetry and painting through the Romantic lens, raging against the alienating effects of industrialisation.

The Lake Poets, most notably William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, were the chief influencers of Romantic poetry. Wordsworth championed the common speech, while Coleridge expanded literary and political theory.

Walter Scott was another Romantic literary luminary, who, alongside Lord Byron, mined drama from the violence of times past. The 1745 Jacobite insurrection served as the setting for Scott’s Waverley, which he published anonymously in 1814 and is considered to be the first historical novel in the Western tradition.

Jane Austen set herself apart from her contemporaries, rejecting gushing emotional prose and plotting for more grounded works laced with cutting satiric comedy as in Sense and Sensibility (1811) and Pride and Prejudice (1813).

Architecture Throughout the Georgian Era

16th-century architect Andrea Palladio was the key influence in the architectural design of the early Georgian Era. The Palladian style hearkened back to the look of Ancient Roman structures, with the use of the classical orders as aesthetic foundations realised through a Venetian perspective.

Colen Campbell spearheaded the transition from English Baroque to Palladian, publishing his designs and thoughts on what ought to be the new British architecture in Vitruvius Britannica (1715-1725).

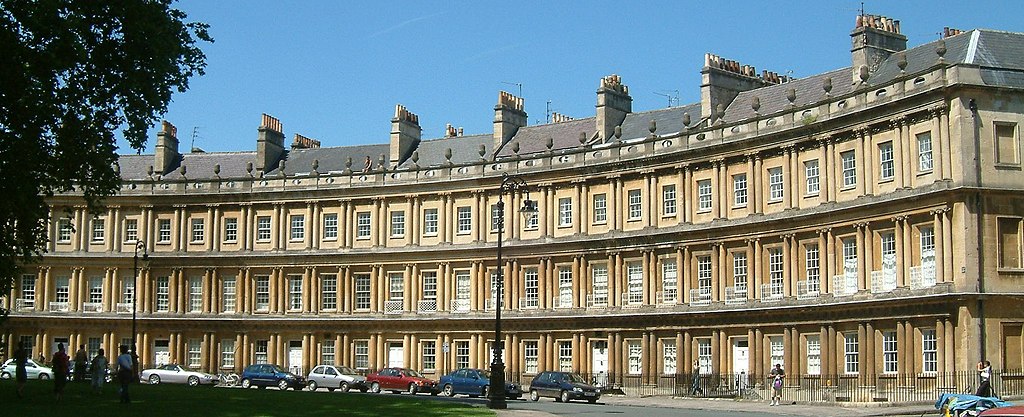

By the late 18th century and early 19th century, British buildings were a mix of freer Neoclassical designs influenced by Grecian, Egyptian, Chinese, and Indian styles, with Robert Adam and John Nash as the leading architects. Gothic Revival architecture was also in vogue, especially for churches, echoing the wave of Romanticism in this particular period.

As towns and cities grew in population, the need for housing that maximised space, while maintaining Neoclassical uniform elegance, led to the creation of terraces. Rows of tall, evenly spaced brick townhouses lined the streets.

Property development boomed, as even the wealthy packed these properties alongside the flourishing middle class, with the former having gardens upfront to differentiate their homes from the latter.

Fashion in the Georgian Era

While the elaborateness of the Baroque style still had a presence in the early 18th century, fashion in the Georgian Era would be defined by the simpler presentation of dress and the expression of one’s individuality.

Women’s Clothing

The understated beauty that came with Neoclassicism made its mark on women's fashion during this period. Dresses had a more natural fit. Corsets remained in use throughout the 18th century but were largely abandoned as the 19th century began.

Loose sack back gowns were the informal dresses of the early to mid 18th century, coming in warm, pastel colours. Formal dresses were lavishly brocaded, featuring ornate stomachers and V-shaped pieces.

Low-neckline gowns over petticoats were typical in late 18th century women's fashion. The French redingote (riding coat) was also popular with British women of stature. False rumps shortly trended to enhance the posterior, at points to a degree that drew satirical mockery in the periodicals.

The turn of the century saw women cling closest to the Classical look. Thin, white, high-waisted, uncorseted chemise gowns were the clothing of choice, evoking the Roman and Grecian statues of the ancient past. This would be known as the Empire style of dress.

Hats, caps, and bonnets were sat on women's tidily kept hair if they weren't piled high during formal events. Long silk gloves and richly decorated fans were common accessories, as were slender parasols to keep the skin fair under the warm sun. Embroidered silk stockings and high-heeled shoes completed women's outfits.

Men's Clothing

The fine embroidery of men's wear during the 17th century disappeared from all but the most formal attire. The cut and fit of the cloth became far more important for the distinguished gentleman. Darker shades were preferred for coats worn over plain white shirts, as well as with waistcoats that matched the pantaloons. Perfectly tied cravats came to be of great import in completing an outfit.

The prevailing ethos in the turn of the 19th century was that of the dandies. High fashion should be accomplished all the while presenting an air of nonchalance. George “Beau” Brummell, Britain's biggest dandy, was considered the style icon of the time.

By the end of the Georgian Era, frock coats replaced tailcoats, corsets were worn for slimmer waists, and coats had paddings on the shoulders and chest to emphasise the masculine shape. Tall silk hats laid on top of short, curly hairstyles.

Jewellery in the Georgian Era

As Britain accumulated wealth through its colonial trade network and newfound industry, the aristocracy enjoyed more opulent events. These grander formal occasions demanded even finer jewellery to be worn with evening wear. As such, the distinction between day and night sets grew larger, making the Georgian Era one of the peaks in British jewellery.

Diamonds were the gemstones to use in night-time parties of the elite until midway through the 18th century. They were set in silver to highlight their brilliance. Paste copies of Diamonds and other precious stones would come into wider use as alternatives, even with the affluent.

When the sun was up, pearls and coloured gems adorned the women of the time. 18ct yellow gold was the preferred metal for setting coloured stones, although rose gold, steel, iron, and pinchbeck were also prevalent. Most jewellery, both Paste and natural gems (including Diamonds!) had closed backs and were foiled so they shone brighter. Sometimes coloured foils were used to enhance the colour of natural Citrines, Garnets and Topaz.

Each piece of this period was crafted entirely by hand. The elaborate designs and manufacturing processes make this apparent, as does the lack of surface pitting.

At the start of the Georgian Era, the Baroque style still held sway over the designs, leading to intricate, heavy, lace-like patterns. This would be followed by asymmetric and light Rococo fashion in the mid-18th century.

As with the rest of the era’s progression to Neoclassicism, jewellery also took a more streamlined look, adopting Greek and Roman motifs such as laurels and grape leaves.

Chatelaines

These were decorative belts where people hung everyday tools such as watches, scissors, and pens. The piece shown below is of enamelled copper, painted with nature scenes reflecting the Romantic aesthetic.

Memorial or Mourning Jewellery

Sentimentality seeped into jewellery in the Georgian Era. People remembered their departed loved ones through memorial or mourning jewellery, which took the form of lockets, pendants, and rings.

Cameos

The love for all things Greek and Roman saw the revival of cameos as parts of jewellery in the 18th and 19th century. Coral, agate, and shells were the base for finely carved reliefs to be included in necklaces and rings.

Pendeloques

A popular earring style during the Georgian era was the pendeloque- a drop type earring set with a long pear shape drop and usually adorned with a bow motif. They were usually set with either Diamonds or Paste, Chrysoberyl or Garnets and pendoloques from France and Iberia are particularly collectable today.

Pendeloques are typically made in 3 separate parts with basic hinge connections, allowing the wearer to attach and detach sections as the occasion called. A simpler look was more practical for daily wear whilst longer, more elaborate designs were fashionable for ladies to wear in the evening.

Necklaces

Women loved to wear necklaces, specifically that of the choker variety, during this period. The rivière-style necklace, featuring individually mounted stones linked close, is one such variation commonly seen on a noble lady.

Fer de Berlin / Berlin Iron

One of the Germans’ contributions to the campaigns against Napoleon was their Gold jewellery. Iron substitutes were given to them in return. Sand cast and lacquered black, such pieces stood apart from its silver and gold contemporaries.

The Legacy of the Georgian Era

The mounting pressures of seemingly never-ending international conflict, rapid industrialisation, and social revolt spanning the reign of five kings did not crush the British people. Even with the less-than-stellar reputation of the House of Hanover as rulers, the United Kingdom came out of the Georgian era with accumulated wealth and power, poised to lead the world in the coming Victorian age.