What is the Victorian Era?

The Victorian Era spans the reign of Queen Victoria from June 20, 1837, until her death on January 22, 1901. For more than 60 years, this period gave birth to a great revolution in the country’s fashions and art—influences and trends that still bleed through to the present.

Queen Victorian by Bassano.

Source: Wikimedia

Those who lived through the Victorian era witnessed rapid changes in various societal spheres, be it through industrial revolutions, socio-political reforms, and scientific discoveries.

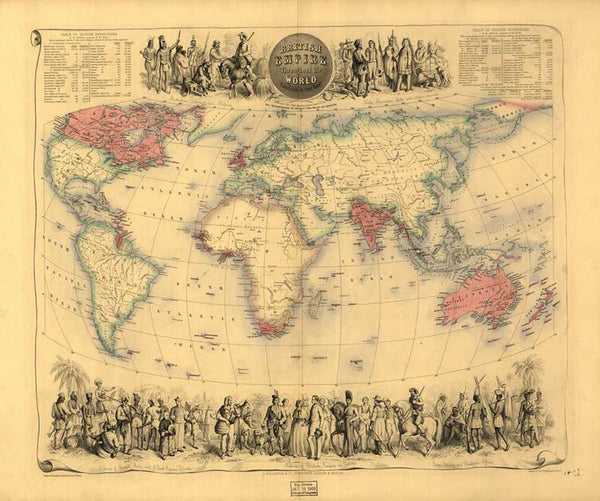

Industry and trade helped turn the British empire into the richest country in the world. Acquiring territories (with the East India Company as one of the most notable) led to Britain owning a quarter of the world’s land and population during this era.

The British Empire throughout the world.

Source: Wikimedia

Back home, romanticism and mysticism helped shape religion and the arts. However, scientific discoveries created a critical lens and led to a more empirical mindset and rigour. And while the middle class grew, so did the class divide and the worsening plight of the poor.

In terms of art, fashion and architecture, the Victorian era can be broken down into three distinct sub-periods. Let’s look at each now.

Early or Romantic Period (1837-1860)

These were politically and socially turbulent years for Britain, as the country evolved from an agricultural to an industrial nation. Notable laws that were passed include the 1832 Reform Bill (redistributed voting rights to areas with growing populations) and the 1846 repeal of the Corn Laws (resulting in lower prices on basic agricultural goods).

Cole Thomas: Romantic Landscape with Ruined Tower.

Source: Wikimedia

However, as industrialisation began, working conditions plummeted, especially for women and children working in mines and factories. As such, art during that time, particularly in literature, depicted the dichotomy between the conditions of the poor and the life of the wealthy. In literature, this is perhaps more famously encapsulated by the works of Charles Dickens (the term ‘Dickensian’ is still used today to describe poor or squalid working or living conditions).

Charles Dickens.

Source: Wikimedia

The Romantic period took its name from the marital bliss between the Queen and her beloved husband, Prince Albert, as well as their nine children. The British population patterned their fashion and jewellery after Queen Victoria’s style. The couple was idealised as the role model for a respectable and loving family, so much so that Prince Albert’s death in 1861 at the age of 42 marked this period’s end.

Mid or Grand Period (1861 to 1879)

Historians recognise the mid-Victorian era as the British Empire’s Golden Years. Income per person grew, industrialisation in textiles and machinery rapidly increased, and the empire further expanded (Australia, India, Canada, to name a few). Exports benefited plenty of British merchants, and colonies supplied cheap raw materials.

The middle class also grew in number during this period, radically affecting the country’s lifestyle, social values, and morals.

The Royal Albert Hall, London.

Source: Wikimedia

Although the economy prospered, poverty remained palpable, especially in rural areas. By the beginning of the 20th century, 25% of the country’s population was poor. Parliament had to enact laws to restrict child labour and dangerous working conditions.

Meanwhile, religious debates grew. The Church of England split into three factions (Evangelical, Broad, and High Church). Scientific discoveries offered critical and alternative ways of looking at the Bible, with Charles Darwin’s The Origin of the Species and The Descent of Man at its forefront.

At the beginning of this period, the Queen mourned Prince Albert’s death and wore black clothing for nearly two decades. The fashion industry followed suit and produced consumer goods in dark and sombre colours.

As a form of protest against the inhumane conditions during the Industrial Revolution, as well as the repetitive designs of consumer goods, the Aesthetic Movement started to emerge and gain traction. Its proponents favoured the pursuit of beauty over socio-political commentary.

The woman in the pink dress exemplifies the departure from the rigidity of the Victorian era. The man with the top hat beside her is Oscar Wilde.

With “art for art’s sake” as its dictum, the movement cast off the Victorian era’s ‘rigid’ style by producing art forms that depicted the freedom of movement and expression. Walter Pater and Oscar Wilde were two of its most prominent figures.

Late or Aesthetic Period (1880 to 1901)

This final period in the long Victorian era continued the affluence of the mid-Victorian era, as the Aesthetic Movement continued to shape the arts, so much so that this period if often referred to at the Aesthetic Period.

Electricity was installed in new buildings. Steam engines and railways crawled the cities. The leisure industry boomed in all the UK’s major cities, with sporting events, music halls, and theatre plays providing sources of entertainment for the middle class.

However, the final decades of the Victorian era saw the British people questioning the process with which this wealth was generated. The political influence of radical thinkers like Karl Marx and Freidrich Engels worried the British industrial and political classes.

Karl Marx.

Source: Wikimedia

People saw the end coming, with artists growing weary of the government’s promises of growth and continuously challenging that optimism. The Queen’s death in 1901 officially closed the Victorian era, with Britain finding itself in a time of uncertainty and social change.

Victorian Era Architecture

Victorian era gave birth to the architecture profession, thanks to the creation of the Institute of British Architects in 1834. With the development of railways, architectural firms reached various parts of the country. Technological advancement also played its part; materials like iron frames, terracotta, polished granite, and plate glass became commercially available.

The Victorian era is renowned for its architectural styles:

Classical or Neoclassical Style

The majority of the buildings in this era were created following the Classical or Neoclassical style, which borrow elements from Greek and Roman architecture; symmetrical designs with columns, for example.

Gothic Revival

Challenging the Classical style, Gothic Revival drew heavy influences from European cathedrals. Anglican churches favoured this style, given its roots in traditional Christianity; so did public government buildings.

Arts and Crafts Movement (1880-1920)

One of the offshoots of the Aesthetic Movement is the Arts and Crafts Movement. Architects who follow this principle designed buildings that are unique, as opposed to those that resemble machine-like structures. They prefer buildings that would naturally fit in their surroundings.

Victorian Era Fashion

Victorian Era Fashion.

Source: Met Museum

Given that Queen Victoria’s reign is the longest among all the monarchs in England’s history (second only to Queen Elisabeth II), there were plenty of styles that came out for men, women, and children.

During the early years, clothes were made by hand. People needed to pay their seamstresses or tailors a visit to get fitted for clothes. Towards the end of the Victorian Era, however, clothes were created using machines.

Women

Women wore bonnets instead of hats. Gigot sleeves (often in three-quarter lengths) were fashionable, as they showed off a woman’s neckline. Skirts, meanwhile, resembled an umbrella from the waist down, using crinolines to maintain the shape.

A long, slim torso with a small waist was considered ideal, with corsets used to complete the hourglass look. Dresses are usually two pieces.

Dresses then evolved to one-piece gowns with narrower shapes. During this time, an outfit had so many layers that a woman needed a maid’s help to put it on. Trailers (or trains) and bustles were also added.

These trends symbolised a woman’s affluent background, as these styles took after Queen Victoria herself.

Men

Men, on the other hand, followed Prince Albert’s style - cinched waists, rounded chests, and flared frock coats that also gave them hourglass figures.

Styles didn’t change much for men, apart from the waistcoat, which was sometimes brightly patterned. Outfits were partnered with hats (for outdoors), a pocket watch, gloves, and handkerchief. For evening wear, a long frock coat is worn together with a bow tie.

Clothing for the poor

Clothes for those in poor families needed to be practical, as they often worked in them. These were patched and sewn as many times as possible to make each piece last longer. Clothes are either wool or cotton and come in dark colours to mask the dirt. Women wore caps/bonnets to keep their hair away from machinery, while children wore hand-me-downs.

Victorian Era Jewellery

Not only was the Victorian Era the golden age for economic prosperity, but it was also a time of growth for the jewellery industry. Technology and artistry came together to produce some of the most beautiful jewellery in the world. For the first time, this was affordable to both the middle and upper classes in British society.

Given the clear demarcation between social classes, the usage of jewellery marked one’s wealth and social status. For instance, young unmarried women were not allowed to wear diamonds and gems (as these were reserved for older women). They could, however, wear simple jewellery.

Queen Victoria, who herself loved clothes and jewellery, set off various trends during the three periods. Let’s examine each in turn:

Early Period (1837-1860)

Georgian period styles were still evident during the early years. Feronnieres were fashionable, as well as headpieces of chain or ribbon with centre jewels worn on the forehead.

The Queen’s predilection to wear multiple rings influenced women of that era to do the same, often stacking multiple pieces of jewellery when possible.

Motifs take inspiration from Queen Victoria and Prince Albert’s love story, with designs symbolising friendship, love, nature, family or happiness. To complement that, decorations often include nature elements (e.g. stars, moon, animals, plants) and decorative frills (e.g. ribbons, fringes, tassels).

Serpents were also a popular design since Prince Albert gave Queen Victoria an engagement ring that featured a serpent with emerald eyes (her birthstone).

Women preferred to wear hair accessories, brooches, necklaces, and bangles. Jewellery materials were confined to silver, diamond, and traditional gems (e.g. garnet, ruby, emerald, amethyst, sapphire, etc.). Delicate enamel work with glass is also used to accent the pieces.

Both pearls and gold were considered extremely valuable at the time. Back then, there was no technology to farm pearls, while gold from California and South Africa has yet to arrive.

Enamelled Gold Brooch, A.W Pugin, c.1848, Source - The Victoria and Albert Museum

Mid Period (1861 to 1879)

Following Prince Albert’s death, Queen Victoria went into mourning. Her style reflected her emotions, as she wore black attire and jewellery. During this period, pieces were referred to as mourning jewellery. It is also not unheard of to weave a loved one’s hair into jewellery, especially those who died, to feel closer to them.

Although these pieces were originally used for mourning, craftsmen were able to create beautiful jewellery despite their sombre and subdued motifs. Large lockets became popular, as did brooches, necklaces, and bracelets. These were then designed with wreaths, angels, or flowers.

Gemstones of choice were often dark in colour, such as deep-red garnet, black onyx, and amethyst. This period also saw influences of Etruscan, Egyptian, and the Renaissance, thanks to archaeological findings during this era.

Renaissance Revival Necklace, Mid 19th Century, Carlo Guilano, Source - The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Although it was Queen Victoria’s mourning that started the trend, memorial jewellery also rose in popularity to commemorate those who died during the rise of industrialisation and poor living conditions in the cities.

Late Period (1880 to 1901)

After a couple of decades of mourning, the British people started to move one, and this was reflected in their jewellery. However, instead of the heavy pieces of the mid-Victorian era, manufacturers focused on smaller and lighter jewellery to fit an active woman’s lifestyle. Delicate rings and bracelets dominated the market, instead of the heavy bangles and necklaces of the previous era.

Motifs now range from the whimsical to the imposing, drawing heavy influences from the Aesthetic Movement. There are insects, stars, dragons, animals, and flowers - any design that would signify romance and good fortune.

Another innovation of the time was the inclusion of tremblers in jewellery to produce the movement and depth of the items as if seen in nature. En tremblant designs originated in Paris but were nevertheless popular in Britain, especially with flower and butterfly motif pieces.

During this time, Queen Victoria’s son Prince Edward and his wife, Princess Alexandra, also became trendsetters. Simple yet sophisticated was the ruling style. Appropriate daytime jewellery would have silver and coloured gemstones, while nighttime jewellery would have diamonds, gold, pearls, or platinum.

Foreign influences were still evident but also extended to embrace Oriental themes, especially from the Japanese.

The Victorian Heritage

Although poverty and unrest marred this era, it is generally agreed amongst historians of the era that Queen Victoria successfully led England into the age of modernity and a time of prosperity for the country, despite the working classes not fully benefiting from this.

Britain’s longest reigning former monarch saw her 63 years in power begin a revolution in art, fashion and jewellery. The aesthetic influences of this period have stood the test of time and continue to shape modern-day art forms.